EXPLORE

Resources on High Rise project are of two kinds:

The Toolbox proposes useful definitions for the reader to fully understand the way we used some recurrent terms within the project. It also give access to the methodological tools we defined, by proposing extract's from the project publications.

We also present here an extended bilbliography from the website's contributions.

Resources on High Rise project are of two kinds:

The Toolbox proposes useful definitions for the reader to fully understand the way we used some recurrent terms within the project. It also give access to the methodological tools we defined, by proposing extract's from the project publications.

We also present here an extended bilbliography from the website's contributions.

The limitation of the visual impact of high-rise buildings by the creation of tower clusters: the example of London

Through the revision of the LVMF in 2011, the GLA recommends clustering high-rise buildings and invites boroughs to identify existing concentrations for intensification.

“New development should safeguard the setting of landmarks (including Strategically Important Landmarks and World Heritage Sites) and, where tall, should ideally contribute to the development or consolidation of clusters of tall buildings that contribute positively to the cityscape. New development should not harm a viewer’s ability to appreciate the Outstanding Universal Value of a World Heritage Site.” (GLA, 2011, p. 29).

From these sophisticated recommendations, as with the 1991 legislation, the principle is to allow negotiation in the planning process. Proposing a tower in a view corridor is not a priori prohibited. However, it is very difficult to get it accepted unless the developer can convince the borough concerned, the municipality and any stakeholders involved that their project is of a very high architectural quality and that it improves the setting of the monuments.

The clusterisation of high-rise buildings in test of negotiated regeneration

The municipalities have integrated the clusterisation of high-rise buildings into their local urban plans (LDF) through specific zoning. However, the recommendation is neither precise nor prescriptive. Moreover, its application is not subject to any control by Greater London. Its principle is intuitively simple: grouped together, towers have a lesser visual impact than isolated ones: the probability of the visual occurrence of an isolated tower in the urban view experience (from the street or from a high point) is higher than for a cluster. Things get more complicated when it comes to defining what a cluster is: are they the clusters identified by planners in the first London Plan? Or are they clusters formed between 2000 and 2014? More technically, from what number of towers is it considered to be a cluster? What should be the maximum spacing between towers? All these questions remain unanswered to this day.

In APPERT Manuel, 2016, Les formes de la métropole : du réseau à la canopée, de la mesure au paysage : Tours, skyline et canopée. Mémoire original pour l’Habilitation à diriger les recherches en géographie, Université Lyon 2, p. 96-97. View on highRise website

Reference

GLA, 2011, London view management Framework, LVMF, London, Greater London Authority.

A condominium is a private residence that is rented out to tenants. A condo is typically located in a residential building or community, but the unit itself is privately owned by an individual who becomes the landlord of that property. The owner of the condo has full say as to who is approved to rent their unit, so renting a condo is more of a personal, one-on-one process than renting an apartment. However, the landlord will not be on site, unless they live in another condo they own in the same building.

What is an apartment?

An apartment is a rental property that is usually owned (not just managed) by a property management company, located in a residential building, complex, or community – whatever the situation may be. In an apartment building, all of the units are the same, the owner is the same, and the tenants all follow the same guidelines for renting a unit in the complex. Every tenant report to the same property manager, who can typically be found in the leasing office with employed leasing agents (to assist current residents and lease other units) at the front of the community or within the complex.

What’s the difference between a condo and an apartment?

So, what makes a condo different from an apartment? In terms of physical attributes, nothing. The difference between the two stems from ownership. You now know that an apartment is housed within a complex (filled with other apartments) that is owned by a single entity, often a corporation, and then leased out to individual tenants.

A condo, however, is owned by an individual and usually managed by either the owner personally, or it lies under the umbrella of that condo community’s homeowner association (HOA), often relying on the assistance of a property management company. So, when you rent a condo, the individual condo owner is your landlord, but when you rent an apartment, the property manager that works for the corporation (the owners) serves as your landlord of sorts, though you may not have as much contact with them directly as you would a landlord because all members of the leasing office assist residents.

Source : https://www.apartments.com/blog/difference-between-renting-an-apartment-or-condo, Quoted In Montès Christian, 2018, High Rise living in the United States: towards vertical exclusion? The case of Dallas-Fort Worth, (presentation document), p. 24.

Condoism is the private (re)production of the contemporary city by refocusing on the center “the self-reinforcing processes re-producing intensification, downtown living and gentrification via condominium-tenure, as well as to the financial-construction nexus at the heart of condominium development, and the social, cultural and political transformations that they are begetting” (Rosen and Walks, 2013)

In Montès Christian, 2018, High Rise living in the United States: towards vertical exclusion? The case of Dallas-Fort Worth, (presentation document), p. 23.

In the case of residential towers, N. Douay notes that towers can be a response to the obligation to sustainable development. By studying the case of Vancouver, one of the North American models of reclaiming the city centre through densification, he shows that the municipality modified its urban planning rules and zoning to 'give developers the opportunity to increase the density of new residential buildings' (Douay, 2015). The translation was the construction of 'high-rise condominiums on sites previously reserved for employment' (Douay, 2015).

Following the work of T. Boddy (2013), he shows how Vancouverism has now become a hybrid urban model, through the circulation of capital, migrants and architectural models between Hong Kong and the Canadian city. By investing massively in Vancouver, Hong Kong developers, such as Concord Pacific, have deployed in Vancouver the podium tower models so common in China. Examples of this model can also be found in London (Pan Peninsula Towers), Toronto, Melbourne, Miami and Warsaw. This model can be compared with condoism (Rosen and Walks, 2014), which is now found in other North American cities, notably Toronto.

In APPERT Manuel, 2016, Les formes de la métropole : du réseau à la canopée, de la mesure au paysage : Tours, skyline et canopée. Mémoire original pour l’Habilitation à diriger les recherches en géographie, Université Lyon 2, p. 39-40.

References

BODDY T., 2013, From Vancouverism to hybrid city, Conférence AAAB, Barcelone, 9 avril.

DOUAY N., 2015, Le « Vancouverism » : hybridation et circulation d’un modèle urbain, Métropolitiques. URL : http://www.metropolitiques.eu/Le-Vancouverism-hybridation-et.html

ROSEN G., WALKS A., 2014, Castles in Toronto’s sky: condo-ism as urban transformation, Journal of Urban Affairs, vol. 37, n°3, p.289-310.

[In the case of the Skyline and High Rise projects,] the high-rise census data was collected by Emporis1. Emporis is a German company founded in 2000 that collects a large amount of data and photographs of high-rise buildings around the world for commercial purposes, especially for the real estate industry. The database produced covered 196 countries and nearly 430,000 buildings in 2012, making it the most comprehensive database on the subject. Access to the data is subject to a fee (3,400 euros in 2012), as are regular updates. I participated in the construction of the database as the French correspondent from 2001 to 2003. Like many other Skyscrapercity.com forum enthusiasts, we filled it with the towers of the geographical areas we covered and with photographs. But the database was privatised by the owner of the forum, who was also the head of the Emporis company. The capitalised data thus became payable and it took me some time to 'digest' this semi-betrayal before I considered paying for it, which I eventually did in 2012. For this reason also, I never acquired the latest updates and preferred to increase it on an ad hoc basis for London and, more recently, Paris.

Other databases: CTBUH and Skyscrapernews

Other databases also list high-rise buildings. The CTBUH2 (Council for Tall Buildings and Urban Habitat), created in 1969, has a database listing 14,000 towers. The association mainly lists the tallest towers, covering South-East Asia particularly well. The English website skyscrapernews.com provides free access to data collected by enthusiasts. The information site created in 2000 lists 6,000 high-rise buildings, with a rather exhaustive coverage of the United Kingdom. These two databases have been part of the source material for the expansion of the Emporis database.

In APPERT Manuel, 2016, Les formes de la métropole : du réseau à la canopée, de la mesure au paysage : Tours, skyline et canopée. Mémoire original pour l’Habilitation à diriger les recherches en géographie, Université Lyon 2, p. 14-15. View on HighRise website

2 Founded in 1969, the CTBUH is an international non-governmental organisation concerned with the construction, operation and planning of high-rise buildings around the world, based at the Illinois Institute of Technology in Chicago. It organises an annual conference that brings together both business and academia, primarily in the field of engineering.

Greater London is the municipality that roughly covers the morphological agglomeration of the metropolis with blurred contours and far from its historic centre. It is the political entity recreated in 2000 by the Labour government and has powers mainly in terms of strategic planning, policing, and transport. The territory of the city covers approximately 1,500 km² with an estimated population of 9 million inhabitants in 2019. It is made up of 32 boroughs, plus the City of London. Within this perimeter, the central and peri-central space is made up of the boroughs within a radius of up to 10km from the hyper-centre.

How to define a tower?

To define a tower, we chose a hybrid method, crossing legal definitions and perceptions of the located object. We defined the tower as an occupied building, at least 160ft (50m) tall or 10 stories. The minimum number of floors attribute compensates for the lack of height information for some of the towers at the base. This height threshold has been arbitrarily defined according to the European context in which towers are relatively rare and the general velum is relatively low. In French urban planning law, the term that comes closest to the tower would be that of high-rise building, defined by Article R122-2 as: "any building whose low floor of the last level is located, in relation to the highest ground level usable for the machinery of the public emergency and fire-fighting services: 160ft (50m) for residential buildings and more than 92ft(28m)for all other buildings". The legal sub-category, ITGH (Immeubles de Très Grande Grande Hauteur), designating buildings with a low floor on the last level of which is at least 656ft (200m)high, was not used to define the towers that were considered because it is too restrictive. A social housing building that is 230ft (70m) tall is considered by many to be a high-rise building. This is because the urban roof sheet is around 65ft (20m) to 98ft (30) tall in European cities. Finally, the databases available to us does not provide information on the morphology of the building. Thus, it was not possible to distinguish between buildings which would be of the bar type and those which would be of the tower type.

In APPERT Manuel, 2016, Les formes de la métropole : du réseau à la canopée, de la mesure au paysage : Tours, skyline et canopée. Mémoire original pour l’Habilitation à diriger les recherches en géographie, Université Lyon 2, p. 14-15. View on HighRise website

Various definition criteria

From a representational point of view, opinions diverge: "a tower is defined by its height in relation to its urban environment", says David Wauthy, director of the SPL EuraLille-Lille, whereas for Coralie Costet, project manager at Adéquation, a design office in charge of urban programming in Lyon, "a tower is only worth calling a tower whenit exceeds the IGH floor". The IGH (Immeuble de Grande Hauteur) floor, which is the regulatory threshold of 164ft (50m) above which a residential building must meet a certain number of standards, has rapidly become a threshold for the buildings we surveyed. Contemporary high-rise residential buildings have a morphology similar to that of the social housing towers in the neighborhoods of large housing estates, which are generally about fifteen stories high and about 148ft (45m) tall [Fortin, 2005]. In order to operationalize the quantitative work, we therefore chose to select all buildings with a minimum height of 148ft (45m).

In Geoffrey Mollé, Manuel Appert and Hélène Mathian, « Le retour de l’habitat vertical et les politiques TOD (Transit Oriented Development) dans les villes françaises : vers une intensification urbaine socialement sélective ? », Espace populations sociétés [Online], 2019/3 | 2019, p.5. View on HighRise website

Since that time IRIS (the term which has replaced IRIS2000) has represented the fundamental unit for dissemination of infra-municipal data. These units must respect geographic and demographic criteria and have borders which are clearly identifiable and stable in the long term.

Towns with more than 10,000 inhabitants, and a large proportion of towns with between 5,000 and 10,000 inhabitants, are divided into several IRIS units. This separation represents a division of the territory. France is composed of around 16,100 IRIS, of which 650 are in the overseas departments.

By extension, in order to cover the whole of the country, all towns not divided into IRIS units constitute IRIS units in themselves.

Source: INSEE website. URL: https://www.insee.fr/en/metadonnees/definition/c1523

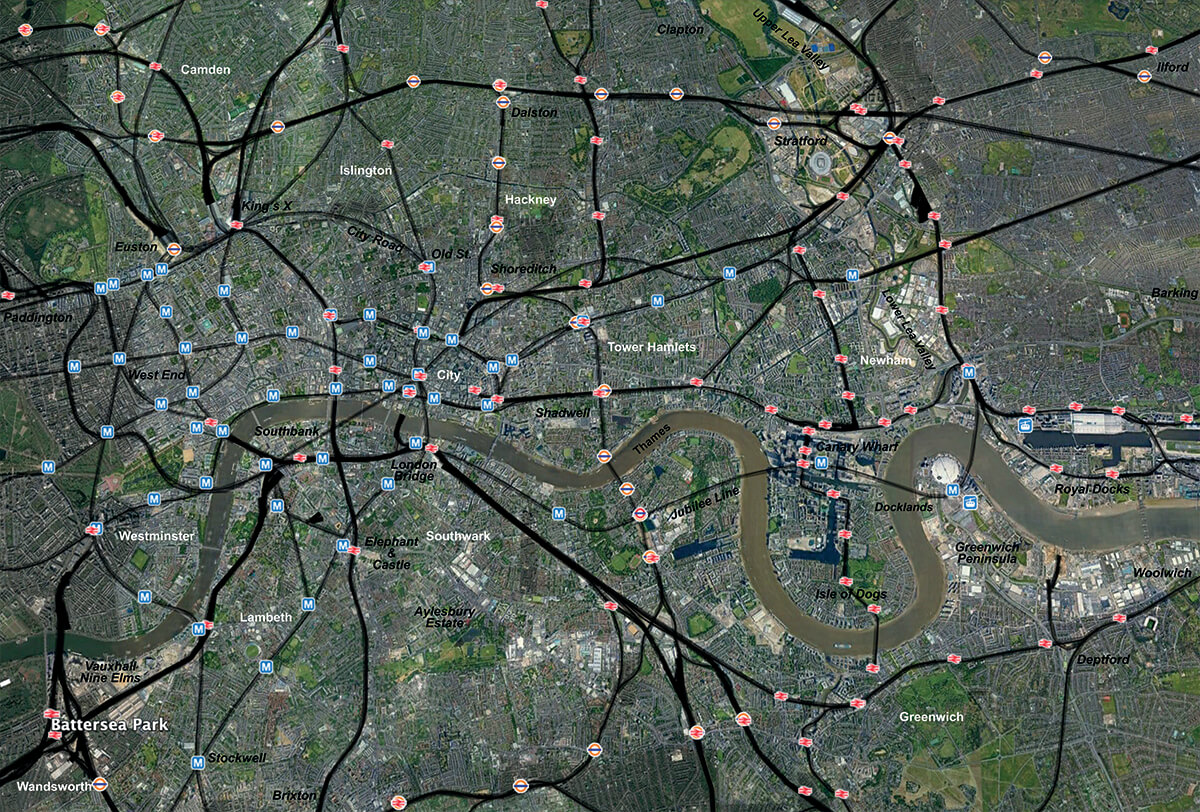

London's 38 Opportunity Areas

Territorial device set up by Greater London to target public-private urban regeneration operations. Section 2.58 of the London Plan (2011) identifies Opportunity Areas of varying size (16 hectares for the Euston Opportunity Area compared to 3,884 hectares for the Upper Lee Valley Opportunity Area), made up of brownfield sites considered as land reserves for the capital. Each can accommodate at least 5,000 jobs and/or 2,500 homes. These areas are characterised by good accessibility - actual or potential - to public transport. The opportunity zones are mainly concentrated in the peripheral parts of the city, close to the economic heart of the metropolis, embodying “Greater London's desire to target urban renewal on areas with relatively high economic potential” (Drozdz, Appert, 2012, p.7).

These areas are, above all, opportunities to correct real estate markets that are considered dysfunctional, those in which land and property values are much lower than their accessibility would suggest. The towers built in these areas are no longer the work of starchitects, as the simple fact of introducing verticality into urban projects is enough to visually mark urban renewal.

In APPERT Manuel, 2016, Les formes de la métropole : du réseau à la canopée, de la mesure au paysage : Tours, skyline et canopée. Mémoire original pour l’Habilitation à diriger les recherches en géographie, Université Lyon 2, p. 60.

Reference

APPERT M., DROZDZ M., 2012, Retour sur l’outillage territorial de la « métropolisation in situ ». Les « zones d’opportunité » de Londres, entre instrument de gouvernance et nouvel ordre spatial, Communication pour le colloque Gouverner la métropole, pouvoirs et territoires, bilans et directions de recherche, Paris, 28, 29 et 30 novembre 2012. URL : https://governingthemetropolis.files.wordpress.com/2012/10/session-1-4-drozdz-appert.pdf

The London example

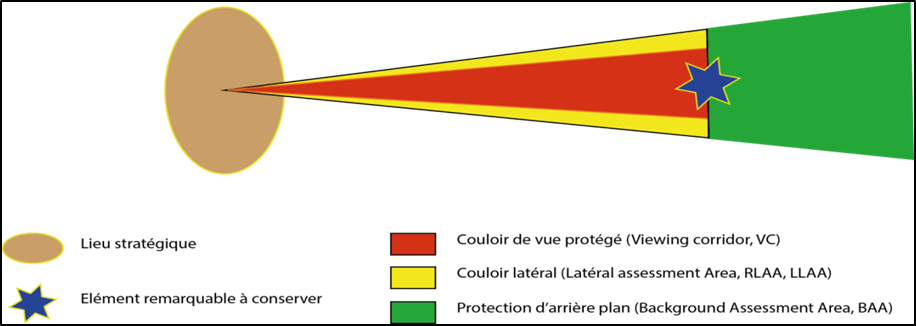

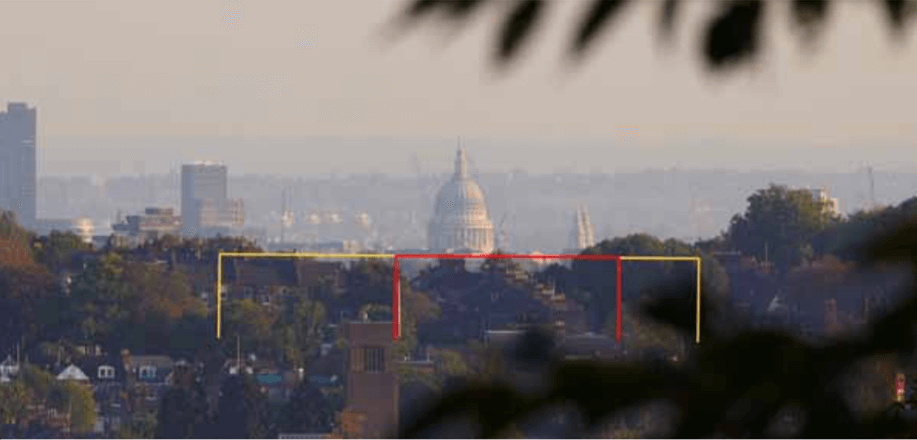

Since the 1930s, there have been explicit planning guidelines for the London skyline. Initially formulated by the City of London in response to attempts to break through the urban canopy near Saint Paul's Cathedral, the legislation was then specified and generalised to the whole city (1956-1991), notably through the use of protected view corridors (since 1991) (Appert, 2008). These protection corridors aim to preserve the view of the monuments in their context from strategic locations in the city. Conservation areas, a zonal regulatory system for heritage preservation, then guarantee the architectural integrity of a given area. However, these two systems are part of a double context. Firstly, that of negotiated urban planning, without a code, and therefore open to interpretation and discussion. Secondly, that of the acculturation of urban planners and city professionals to the perspectives of the Townscape movement, which emphasises the staging, the compositions and the picturesque in the landscape approach. (...)

The preservation of monumental views has its origin in the protection of the silhouette of St. Paul's Cathedral. Pictorial representations of the cathedral by Canaletto, Turner and Claes Van Visscher, or photographs of the building standing amidst the smoke of Luftwaffe bombing in the 20th century, have helped to construct a landscape in which the cathedral symbolises both London and the spirit of conquest or resistance. Thus, St Paul's still monopolises the attention of the curators of built heritage and its staging as a prominent and majestic monument. Since the 1960s, successive legislations has extended the protection by view corridors to other emblematic buildings of the city (Parliament, Tower of London...)1 .

The visibility of the monuments was to be ensured by view corridors from strategic points in the urban area. In these view corridors, the height of buildings is limited so that the silhouette of the monuments is defined against the sky.

In APPERT Manuel, 2016, Les formes de la métropole : du réseau à la canopée, de la mesure au paysage : Tours, skyline et canopée. Mémoire original pour l’Habilitation à diriger les recherches en géographie, Université Lyon 2, p. 94-96. View on HighRise website

The definition of high-value settlement areas

The example of the legislation on view corridors on this subject, the only flagship measure of the GLA (Greater London Authority) regarding the territorial implantation of towers, has rapidly become a delimitation of potentially verticalizable zones and therefore almost an aid for private actors in search of spaces to implant high added value projects. It could be added that these rules have not always been followed to the letter, as shown by the example of the Shard, the tallest tower in Europe, but in the middle of one of the most highly regarded view corridors because it is adjacent to St Paul's Cathedral.

In Mollé Geoffrey, De la tour résidentielle au signal d’intensité urbaine : La fabrique des lieux verticaux dans les villes françaises, mémoire de Master de deuxième année, mention Villes et environnements urbains, Université Lyon 2 Lumière, 2017, p. 59. View on HighRise website

Transit Oriented Development (TOD) formalises measures aimed at reducing urban sprawl and the dependence on the automobile as it was gradually established during the Thirty Glorious Years. Whereas the Athens Charter, enacted in 1933 and amended by Le Corbusier in 1941, stipulated a separation between the space of housing (vertical), that of work, leisure and transport infrastructures in a functionalist vision of post-World War II urban growth, TOD policies no longer consider transport through its infrastructural dimension but as mobilities giving space its value.

In the continuity of the 1994 Aalborg Charter, the anti-Athens Charter for the environmental sustainability of cities [Theys and Emelianoff, 2001], mobility is less motorised, chosen and embedded in mixed urban spaces. The tools developed to plan mixed and dense neighbourhoods near strategic nodes of public transport networks would thus offer 'a simultaneous response to both metropolitan and local urban planning and sustainable mobility issues' [Dushina, Paulhiac, Scherrer, 2015, p. 69]. Peter Calthorpe [1993, p. 56], the initiator of TODs, defined them as mixed-use neighbourhoods near public transport nodes in the pericentre of cities.

TODs combine residential, commercial, service, recreational and civic functions in neighbourhoods where the use of soft modes should be favoured. According to Peter Calthorpe, TODs are based on four principles. First, a mix of housing, services and jobs are articulated around public spaces that link public transport nodes. Secondly, the built and pedestrian environment must be attractive and safe for users of soft modes. Thirdly, the development of compact TODs should be planned on a metropolitan scale and carried out along public transport corridors, on vacant sites or sites to be redeveloped (brownfields). Finally, these areas should preferably be located within the built-up area of cities in order to contain urban sprawl.

In Mollé Geoffrey, Appert Manuel et Mathian Hélène, « Le retour de l’habitat vertical et les politiques TOD (Transit Oriented Development) dans les villes françaises : vers une intensification urbaine socialement sélective ? », Espace populations sociétés [Online], 2019/3 | 2019, p.14-15. View on HighRise website

References

THEYS Jacques, EMELIANOFF Cyria, 2001, Les contradictions de la ville durable. Le Débat, n°113, p. 122-135.

DUSHINA Anna, PAULHIAC SCHERRER Florence, Franck SCHERRER, 2015, Le TOD comme instrument territorial de la coordination entre urbanisme et transport : le cas de Sainte-Thérèse dans la région métropolitaine de Montréal. Flux n° 101/102, p. 69-81.

CALTHORPE P., 1993, The Next American Metropolis: Ecology, Community, and the American Dream, Princeton: Princeton Architectural Press. p. 56.

A territorial division established within the framework of the European Espon project

The Espon1 project "European Spatial Observatory Network on territorial development and cohesion" is a programme created in 2007 and funded by the European Union under the European cohesion policy. Its aim is to support a regional policy focused on territorial cohesion. In this logic, this project is led to conduct comparative analyses of the territories, to enrich itself with statistical data, etc.

In order to promote the comparability of data on a European scale, this programme has developed efficient territorial breakdowns allowing the presentation of relevant and harmonised information.

Thus, various data (free of charge) are proposed on the Espon2 website, in particular data on European agglomerations and geometric data that divides the European territory into coherent units.

The main ones are "morphological urban areas for cities with more than 10,000 inhabitants" (UMZ), "morphological urban areas for cities with more than 20,000 inhabitants" (MUA) and "functional urban areas" (FUA), all with basic population indicators, some with economic and social data.

Morphological urban areas are defined on the basis of physical criteria of building continuity, while functional urban areas focus not only on the building but also on all the functional spaces attached to it (mainly according to commuting).

The relevance of the UMA division for an analysis on a global territorial scale

Of these three different data, the UMA would seem to be the most coherent for an analysis on a global scale.

The threshold of 20,000 inhabitants is objectively much more coherent for the subject linked to the context of metropolisation. It makes it possible to exclude conurbations in which high-rise buildings are not necessarily linked to a global context of return of high-rise buildings.

Moreover, the morphological criterion is important. The UMA is undoubtedly the data that most closely resembles the urban fabric of cities, as the functional urban areas are far too large.

[Furthermore,] This category does not cover Balkan Europe (Croatia, Bosnia, Macedonia, Serbia, Montenegro, Albania and Bulgaria) nor Russia, Ukraine and Belarus. Similarly, towers located in functional regions are excluded, only those located within morphological agglomerations are retained.

In APPERT Manuel, 2016, Les formes de la métropole : du réseau à la canopée, de la mesure au paysage : Tours, skyline et canopée. Mémoire original pour l’Habilitation à diriger les recherches en géographie, Université Lyon 2, p. .32-33. View on HighRise website

A - B - C - D - E - F - G - H - I - J - K - L - M - N - O - P - Q - R - S - T - U - V - W - X - Y - Z

ALLEN Scott J., 2011, Emerging Cities of the Third Wave, City 15 (2-3): 289-321.

ALMI, S., Urbanisme et colonisation: présence française en Algérie, Mardaga, Paris, 2002.

ANDERSON, Jon. 2004. “Talking Whilst Walking: A Geographical Archaeology of Knowledge.” Area 36 (3): 264–261.

APPERT M., 2008, Ville globale versus ville patrimoniale ? Des tensions entre libéralisation de la skyline de Londres et préservation des vues historiques, Revue Géographique de l’Est, vol.48, n°1-2. URL : https://rge.revues.org/1154

APPERT M., DROZDZ M., 2010, La géopolitique locale-globale aux marges de la City de Londres : conflits autour des projets de renouvellement urbain de Bishopsgate, Hérodote, n°137, p.119-134.

APPERT Manuel, 2011, Les nouvelles tours de Londres comme marqueurs des mutations d’une métropole globale. Observatoire de la société britannique [En ligne], 11, p.105-122. URL : http://osb.revues.org/1243 ; DOI : 10.4000/osb.1243

APPERT M., DROZDZ M., 2012, Retour sur l’outillage territorial de la « métropolisation in situ ». Les « zones d’opportunité » de Londres, entre instrument de gouvernance et nouvel ordre spatial, Communication pour le colloque Gouverner la métropole, pouvoirs et territoires, bilans et directions de recherche, Paris, 28, 29 et 30 novembre 2012. URL : https://governingthemetropolis.files.wordpress.com/2012/10/session-1-4-drozdz-appert.pdf

APPERT M., 2012b, Les nouvelles tours de Londres comme marqueurs des mutations d’une métropole globale, Observatoire de la Société britannique, n°10.

APPERT Manuel, 2015, Le retour des tours dans les villes européennes. Métropolitiques, URL : https://www.metropolitiques.eu/Le-retour-des-tours-dans-les.html

APPERT M., MONTES C., 2015, Skyscrapers and the redrawing of the London skyline: a case of territorialisation through landscape control. Articulo-Journal of Urban Research (Special issue 7). URL : https://articulo.revues.org/2784

APPERT Manuel, 2016, Les formes de la métropole : du réseau à la canopée, de la mesure au paysage : Tours, skyline et canopée. Mémoire original pour l’Habilitation à diriger les recherches en géographie, Université Lyon 2, 293 p. View on Highrise website

APPERT Manuel, HURÉ Maxime, LANGUILLON Raphaël, 2017, Gouverner la ville verticale : entre ville d’exception et ville ordinaire. Géocarrefour [Online], 91/2. URL : http://journals.openedition.org/geocarrefour/10013.

APPERT Manuel, MONTÈS Christian et DROZDZ Martine, 2017, « Enjeux de l'exploration culturelle des hauteurs urbaines », Géographie et cultures [En ligne], 102, URL : http://journals.openedition.org/gc/5175 ; DOI : https://doi.org/10.4000/gc.5175

APPERT Manuel, DROZDZ, Martine and HARRIS Andrew, 2018. “High-Rise Urbanism in Contemporary Europe.” Built Environment 43 (4): 469–80. https://doi.org/10.2148/benv.43.4.469.

APPERT Manuel, MOLLÉ Geoffrey et MATHIAN Hélène, 2019, « Le retour de l’habitat vertical et les politiques TOD (Transit Oriented Development) dans les villes françaises : vers une intensification urbaine socialement sélective ? », Espace populations sociétés [En ligne], n°3, URL : http://journals.openedition.org/eps/9256 ; DOI : https://doi.org/10.4000/eps.9256 View on Highrise website

ATKINSON, Rowland, and Sarah Blandy. 2016. Domestic Fortress. Manchester: Manchester University Press. URL: http://www.manchesteruniversitypress.co.uk/9781784995317/.

AUGE, M., 1986 (2013), Un ethnologue dans le métro, Pluriel, 121p.

AUGÉ, M., 1992, Non-lieux. Introduction à une anthropologie de la surmodernité, Editions du Seuil, La Librairie du XXIsiècle, Paris, 149p.

BALLESTER P., 2016, Habiter en Méditerranée, la métropole à l’épreuve du développement durable, Les Annales de la recherché urbaine, n°111, p.112-123.

BAVOUX, JJ., BAUCIRE, F., CHAPELON, L., ZEMBRI, P., 2005, Géographie des transports, Armand Colin, Paris, 227p.

BAXTER, Richard, and BRICKELL Katherine. 2014. “For Home UnMaking.” Home Cultures 11 (2): 133–43. URL: https://doi.org/10.2752/175174214X13891916944553.

BAXTER Richard, 2017, “The High-Rise Home: Verticality as Practice in London”, International Journal of urban and regional research, DOI: 10.1111/1468-2427.12451.

BENNETT, Jane. 2010. Vibrant Matter: A Political Ecology of Things. Duke University Press. URL: https://ezp.lib.unimelb.edu.au/login?url=https://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&db=cat00006a&AN=melb.b5938683&site=eds-live&scope=site.

BENTAYOU Gilles, PERRIN Emmanuel, RICHERAL Cyprien, 2015, Contrat d'axe et Transit-Oriented Development : quel renouvellement de l'action publique en matière de mobilité et d'aménagement ? (Point de vue d'acteurs). Flux, 3 (N° 101-102), p. 111-123.

BERLAND-BERTHON A., 2009, La démolition des logements sociaux, Histoire urbaine d’une non-politique publique, Lyon, Editions du Certu, 488p.

BERNARD, A., 2014, Lifted, A Cultural History of the Elevator. New York University Press, 309p.

BLUNT, Alison, 2008. “The ‘Skyscraper Settlement’: Home and Residence at Christodora House.” Environment and Planning A 40 (3): 550–71. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1068/a3976.

BODDY T., 2013, From Vancouverism to hybrid city, Conférence AAAB, Barcelone, 9 avril.

BOREL C., 2014, Le retour des tours dans les villes européennes : analyse statistique et cartographique, mémoire de Master 1, Université Lyon 2, 109p.

BOTEA Bianca, 2014, « Expérience du changement et attachements. Réaménagement urbain dans un quartier lyonnais (la Duchère) ». Ethnologie française Vol. 44, no 33 : p. 461‑467.

BOTEA Bianca, MONGEARD Laëtitia et SERRA Lise, 2019, « Connaissances par proximité dans la recherche sur la rénovation urbaine. », EspacesTemps.net [Online], Traverses, URL: https://www.espacestemps.net/articles/connaissances-par-proximite-dans-la-recherche-sur-la-renovation-urbaine/; DOI: 10.26151/espacestemps.net-5ezs-v534.

BOUDREAU J.-A. et LABBE D., 2011, Les nouvelles zones urbaines à Hanoi : Ruptures et continuités avec la ville, Cahiers de géographie du Québec, 55(154), 131–149.

BOURDIEU Pierre, 1993, Les effets de lieu, p. 249-261, in BOURDIEU P. (dir.), La Misère du monde, Paris, Seuil, coll. « Libre Examen », 960 p.

BREGVIGLIERI Marc and TROM Danny, 2003, « Troubles et tensions en milieu urbain. Les épreuves citadines et habitantes de la ville », in Les sens du public : publics politiques et médiatiques, D. Céfaï et D. Pasquier (dir.), PUF, pp. 399-416.

CAIRNS Stephen, JACOBS Jane M. and STREBEL Ignaz, 2007. “‘A Tall Storey ... but, a Fact Just the Same’: The Red Road High-Rise as a Black Box.” Urban Studies 44 (3): 609–29. URL: https://doi.org/10.1080/00420980601131910.

CALTHORPE P., 1993, The Next American Metropolis: Ecology, Community, and the American Dream, Princeton: Princeton Architectural Press.

CATCHPOLE T., 1987, London Skylines: A study of High Buildings and Views, London, London Research Centre, Research and Studies Series, vol.33.

CERISE E., 2009, Fabrication de la ville de Hanoi entre planification et pratiques habitantes : conception, production et réception des formes bâties, thèse de doctorat présentée à l’Université de Paris VIII.

CHABARD P., PICON-LEFEBVRE V., 2013, La Défense, dictionnaire et atlas, 2 volumes, Paris, Parenthèses.

CHABARDÈS Alexandre, 2018, «Ressentir la verticalité : étude de cas de la Tour Panoramique de la Duchère», Mémoire de Master 2 en anthropologie, Université Lyon 2. View on Highrise website

CHAPELON, L., BAVOUX, JJ., BAUCIRE, F., ZEMBRI, P., 2005, Géographie des transports, Armand Colin, Paris, 227p.COHEN, J.-L., N. Oulebsir, and Y. Kanoun, Alger : Paysage urbain et architectures, 1800-2000, Editions de l’Imprimeur, Paris, 2003.

CLIFFORD James, 1983, « De l’autorité en ethnographie » L’Ethnographie, n°2, p. 87-108, republié dans Céfaï, Daniel (textes réunis, présentés et commentés par). 2003. L’enquête de terrain. Paris : La Découverte, M.A.U.S.S.

COQUERY, M., « Quartiers périphériques et mutations urbaines », Méditerranée, Vol. 6, n° 4, p. 285–298, mis en ligne en 1965. URL: https://www.persee.fr/doc/medit_0025-8296_1965_num_6_4_1175 ; DOI: 10.3406/medit.1965.1175.

COSTE A., 1997, Le modèle en architecture : entre rétrospective et prospective, in Cahiers de la Recherche Architecturale, n°40 “Imaginaire technique”, Marseille, Parenthèses, pp.19- 28.

COSTELLO L., 2005, From prisons to penthouses: the changing images of high-rise living in Melbourne, Housing Studies, vol.20, n°1, p.49-62.

CROMMELIN Laura, PINNEGAR Simon, RANDOLPH Bill, TROY Laurence and EAST-EASTHOPE Hazel, 2020. “Vertical Sprawl in the Australian City: Sydney’s High-Rise Residential Development Boom.” Urban Policy and Research, January, 1–19. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1080/08111146.2019.1709168.

CULICIU Cristian, 2015, “Urbanizare și sistematizare urbană în România Comunistă”, in A. Macavei & D. M. Dăian (dir.), Fragmente din trecut. Tinerii cercetători și istoria, pp. 317-331, Cluj-Napoca: Presa Universitară Clujeană.

DAVIDSON Mark and LEES Loretta, 2005, New-build gentrification and London’s riverside renaissance, Environment and Planning A, vol.37, p.1165-1190.

DE CERTEAU, M., 1990, L’invention du quotidien, 1. Arts de faire, Gallimard, Folio, Paris, 347p.

DECOSTER F. et KLOUCHE D., 1997, Hanoi: Portrait de ville, Institut Français d’Architecture.

DE LEON, Jason Patrick, and COHEN Jeffrey H. 2005. “Object and Walking Probes in Ethnographic Interviewing.” Field Methods 17 (2): 200–204. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1177/1525822X05274733.

DELYSER, Dydia, and SUI Daniel, 2013. “Crossing the Qualitative- Quantitative Divide II: Inventive Approaches to Big Data, Mobile Methods, and Rhythmanalysis.” Progress in Human Geography 37 (2): 293–305. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1177/0309132512444063.

DE VOS, Els. 2010. “Living with High-Rise Modernity: The Modernist Kiel Housing Estate of Renaat Braem, A Catalyst to a Socialist Modern Way of Life?” Home Cultures 7 (2): 135–58. DOI: https://doi.org/10.2752/175174210X12663437526098.

DIDELON C., 2010, Une course vers le ciel. Mondialisation et diffusion spatio-temporelle des gratte-ciel, Mappemonde, n°99. URL: http://mappemonde.mgm.fr/num27/articles/art10301.html.

DORIGNON Louise, High-rise living in the middle-class suburb: a geography of tactics and strategies, PhD thesis in Geography and Philosophy, University of Melbourne / Université Lyon 2 Lumière, May 2019. View on Highrise website

DORIGNON Louise, and NETHERCOTE, Megan, 2020. “Disorientation in the Unmaking of High-Rise Homes.” Transactions of the Institute of British Geographers n/a (n/a): 1–15. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1111/tran.12427.

DOUAY N., 2015, Le « Vancouverism » : hybridation et circulation d’un modèle urbain, Métropolitiques. URL: http://www.metropolitiques.eu/Le-Vancouverism-hybridation-et.html.

DROZDZ M., APPERT M., 2010, La géopolitique locale-globale aux marges de la City de Londres : conflits autour des projets de renouvellement urbain de Bishopsgate, Hérodote, n°137, p.119-134.

DROZDZ M., APPERT M., 2012, Retour sur l’outillage territorial de la « métropolisation in situ ». Les « zones d’opportunité » de Londres, entre instrument de gouvernance et nouvel ordre spatial, Communication pour le colloque Gouverner la métropole, pouvoirs et territoires, bilans et directions de recherche, Paris, 28, 29 et 30 novembre 2012. URL: https://governingthemetropolis.files.wordpress.com/2012/10/session-1-4-drozdz-appert.pdf

DROZDZ Martine, 2014, Regeneration b(d)oom. Territoires et politique de la régénération urbaine par projet à Londres, Thèse de doctorat en Géographie, Université Lyon 2.

DROZDZ M., 2014, La construction territoriale de la compétition et de la redistribution à Londres entre rééchelonnement (rescaling) de l’Etat et enclavement stratégique, in LE BLANC et al. (dir.), Métropoles en débat : (dé)constructions de la ville compétitive, Presses Universitaires de Paris Ouest.

DROZDZ Martine, APPERT Manuel et MONTÈS Christian, 2017, « Enjeux de l'exploration culturelle des hauteurs urbaines », Géographie et cultures [En ligne], 102, URL: http://journals.openedition.org/gc/5175 ; DOI : https://doi.org/10.4000/gc.5175.

DROZDZ, Martine, APPERT Manuel, and HARRIS Andrew, 2018. “High-Rise Urbanism in Contemporary Europe.” Built Environment 43 (4): 469–80. DOI: https://doi.org/10.2148/benv.43.4.469.

EAST-EASTHOPE Hazel, CROMMELIN Laura, PINNEGAR Simon, RANDOLPH Bill and TROY Laurence, 2020. “Vertical Sprawl in the Australian City: Sydney’s High-Rise Residential Development Boom.” Urban Policy and Research, January, 1–19. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1080/08111146.2019.1709168.

FINCHER Ruth, 2007, Is High-rise innovative? Developers’ contradictory narratives of high-rise housing in Melbourne, Urban Studies, vol.44, p.631-644.

FOUCHIER Vincent, 2010 "Chapter 7 - Spatial stakes of the Ile-de-France metropolis", Laurent Cailly ed, La France, une géographie urbaine. Armand Colin, pp. 129-148.

GARRETT Bradley L., 2011. “Videographic Geographies: Using Digital Video for Geographic Research.” Progress in Human Geography 35 (4): 521–41. https://doi.org/10.1177/0309132510388337.

GEERTZ Clifford, 1998, «The Dense Description», Inquiry [Online], No. 6, URL: http://journals.openedition.org/enquete/1443; DOI: https://doi.org/10.4000/enquete.1443.

GIBSON James J., (1979) 2014, Approche écologique de la perception visuelle, édition Dehors.

GIBSON Chris, KERR Sophie-May and KLOCKER Natascha, 2018. “Parenting and Neighbouring in the Consolidating City: The Emotional Geographies of Sound in Apartments.” Emotion, Space and Society 26: 1–8. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.emospa.2017.11.002.

GIBSON Chris, KERR Sophie-May and KLOCKER Natascha, 2020. “From Backyards to Balconies: Cultural Norms and Parents’ Experiences of Home in Higher-Density Housing.” Housing Studies, January, 1–23. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1080/02673037.2019.1709625.

GILBERT Pierre, 2012, L'effet de légitimité résidentielle : un obstacle à l'interprétation des formes de cohabitation dans les cités hlm. Sociologie, 2012/1 (Vol. 3), p. 61-74.

GLA, 2004, The London plan, London, Greater London Authority.

GLA, 2009, Vauxhall-Nine Elms-Battersea Opportunity Planning Framework Consultancy Draft, London, Greater London Authority.

GLA, 2011, London view management Framework, LVMF, London, Greater London Authority.

GLEESON J, 2011, Housing: A growing city, Focus on London 2011, London, GLA Economics.

GODO P., 1999, L’architecture et le corps, Le Philosophoire, 1999/1 (n° 7), p. 43-54. DOI: 10.3917/phoir.007.0043. UR : https://www.cairn.info/revue-le-philosophoire-1999-1-page-43.htm.

GOFFMAN, E., 1973, La mise en scène de la vie quotidienne ; vol. I : La présentation de soi, 256 p. Les éditions de minuit, Le sens commun Paris, 1973 ; vol. II : Les relations en public, 376 p., Les éditions de minuit, Le sens commun, Paris, 1973 ; vol. III : Les rites d’interaction, Les éditions de minuit, Le sens commun, Paris, 1974, 236p.

GOSH Sumata, 2014, “Everyday Lives in Vertical Neighbourhoods: Exploring Bangladeshi Residential Spaces in Toronto’s Inner Suburbs”, International Journal of Urban and Regional Research, vol. 38.6, DOI:10.1111/1468-2427.12170

GOTTMAN J., 1966, Essais sur l’Aménagement de l’Espace habité, Paris, Laye, Mouton et Co, 348p.

GRAHAM Stephen and HEWITT Lucy, 2013. “Getting off the Ground: On the Politics of Urban Verticality.” Progress in Human Geography 37 (1): 72–92. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1177/0309132512443147.

GRAHAM S., 2015b, Luxified skies: How vertical urban housing became an elite preserve, City: analysis of urban trends, culture, theory, policy, action, vol.19, n°5, p.618-645.

GRAHAM Stephen, 2016, Vertical: the city from above and below, Londres and New-York, Verso, 276 p.

GRAHAM, S., 2016, Vertical - The City from Satellites to Bunkers. Verso Books, 416p.

GRAHAM Stephen, 2018. “Elite Avenues.” City, January, 1–24. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1080/13604813.2017.1412190.

GRILLET AUBERT, A., GUTH, S., CLEMENT, P., 2001, « Transport et architecture du territoire, Etat des lieux et perspectives de recherche », Rapport de recherche, 175p.

HARKER Christopher, 2014, “The only way is up? Ordinary Topologies of Ramallah”, International Journal of Urban and Regional Research, vol.38.1, DOI: doi.org/10.1111/1468-2427.12094

HARRIS, Andrews, 2015, Vertical Urbanisms. Opening up geographies of the three-dimensional city, Progress in Human Geography, vol. 39, n° 5, pp.601-620. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1177/0309132514554323.

HARRIS Andrew, DROZDZ Martine and APPERT Manuel, 2018. “High-Rise Urbanism in Contemporary Europe.” Built Environment 43 (4): 469–80. DOI: https://doi.org/10.2148/benv.43.4.469.

HARTMUT, R., 2010, Accélération. Une critique sociale du temps, La Découverte, Paris, 486p.

HARVEY David, 1989, From managerialism to entrepreneurialism: the transformation of urban governance in late capitalism. Geografiska Annaler B, 71(1), p. 3-17.

HARVEY David, 2006. Spaces of Global Capitalism : Towards a Theory of Uneven Geographical Development. London ; New York: Verso. URL: https://ezp.lib.unimelb.edu.au/login?url=https://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&db=edshlc&AN=edshlc.009987451-2&site=eds-live&scope=site.

HARVEY David., 2008, Géographie de la domination, Paris, Les Prairies Ordinaires, 118p.

HAY Lain, 2016. Qualitative Research Methods in Human Geography. Fourth edition. Oxford University Press. URL: https://ezp.lib.unimelb.edu.au/login?url=https://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&db=cat00006a&AN=melb.b6331137&site=eds-live&scope=site.

HEWITT Lucy and GRAHAM Stephen, 2013. “Getting off the Ground: On the Politics of Urban Verticality.” Progress in Human Geography 37 (1): 72–92. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1177/0309132512443147.

HOLMES S., 2004, The history and effects of changes, past and present, to London’s skyline. URL: http://wwwusers.brookes.ac.uk/01231893.

HURÉ Maxime, APPERT Manuel et LANGUILLON Raphaël, 2017, Gouverner la ville verticale : entre ville d’exception et ville ordinaire. Géocarrefour [Online], 91/2. URL: http://journals.openedition.org/geocarrefour/10013.

IBOS S., 2015, Négocier le skyline de Londres à l’ère de la régénération : le cas de Vauxhall-Nine Elms, mémoire de Master 2, ENS de Lyon, 119p.

INGOLD Tim, 2000, The perception of the environment: essays on livelihood, dwelling and skill, London, Routledge.

INGOLD Tim, 2011, Being alive: essays on movement, knowledge and description, London, Routledge.

INGOLD Tim, 2013, Marcher avec les dragons, Bruxelles, édition Zones Sensibles.

ISAAC Joseph, 2002. « Le nomade, la gare et la maison vue de toutes parts » Communications, vol. 73, n°1, p. 149-162.

ISAAC Joseph, 2006, « Résistances et sociabilités » in L’athlète moral et l’enquêteur modeste, Economica, Collection Etudes sociologiques.

JACOBS, J., 2006, « A geography of big things. cultural geographies », SAGE Publications, vol. 13, n°1, pp.1-27.

JACOBS Jane M., CAIRNS Stephen, and STREBEL Ignaz, 2007. “‘A Tall Storey ... but, a Fact Just the Same’: The Red Road High-Rise as a Black Box.” Urban Studies 44 (3): 609–29. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1080/00420980601131910.

JAMES Evans and JONES Phil, 2011. “The Walking Interview: Methodology, Mobility and Place.” Applied Geography 31 (2): 849–58. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apgeog.2010.09.005.

KADDOUR R., 2015, Les représentations complexes des tours d’habitat populaire. La trajectoire en trois actes de la tour Plein-Ciel. Saint-Étienne, Métropolitiques. URL: https://www.metropolitiques.eu/Les-representations-complexes-des.html.

KAUFMANN, JC., 1989, La vie ordinaire, voyage au coeur du quotidien, Paris, Greco.

KEIL Roger, LEHRER Ute and KIPFER Stephan, 2010, Reurbanisation in Toronto : Condominium boom and social housing revitalization. DisP- The planning Review, 181, p. 81-90.

KERR Sophie-May, GIBSON Chris, and KLOCKER Natascha, 2018. “Parenting and Neighbouring in the Consolidating City: The Emotional Geographies of Sound in Apartments.” Emotion, Space and Society 26: 1–8. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.emospa.2017.11.002.

KERR Sophie-May, GIBSON Chris, and KLOCKER Natascha, 2020. “From Backyards to Balconies: Cultural Norms and Parents’ Experiences of Home in Higher-Density Housing.” Housing Studies, January, 1–23. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1080/02673037.2019.1709625.

KLOUCHE D. et DECOSTER F., 1997, Hanoi: Portrait de ville, Institut Français d’Architecture.

KUSENBACH Margarethe. 2003. “Street Phenomenology: The Go-Along as Ethnographic Research Tool.” Ethnography 4 (3): 455–85. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1177/146613810343007.

KWONG-WING C. et al., 2007, Determining Optimal Building Height, Urban Studies, vol.44, n°3, p.591-607. URL: www.researchgate.net/journal/0042-0980.

LABBE D. et BOUDREAU J.-A., 2011, Les nouvelles zones urbaines à Hanoi : Ruptures et continuités avec la ville, Cahiers de géographie du Québec, 55(154), 131–149.

LANGUILLON Raphaël, HURÉ Maxime et APPERT Manuel, 2017, Gouverner la ville verticale : entre ville d’exception et ville ordinaire. Géocarrefour [Online], 91/2. URL: http://journals.openedition.org/geocarrefour/10013.

LATHAM Alan and McCORMACK Derek P., 2009. “Thinking with Images in Non-Representational Cities: Vignettes from Berlin.” Area 41 (3): 252–62. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1475-4762.2008.00868.x.

LATHAM Alan, 2016. “Respondend Diaries.” In Key Methods in Geography, Third edition. SAGE.

LAWHON Mary and PIERCE Joseph, 2015. “Walking as Method: Toward Methodological Forthrightness and Comparability in Urban Geographical Research.” The Professional Geographer 67 (4): 655–62. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1080/00330124.2015.1059401.

LE CORBUSIER, 1925, Urbanisme, Paris, Crès,pp. 219.

LEES L., DAVIDSON M., 2005, New-build gentrification and London’s riverside renaissance, Environment and Planning A, vol.37, p.1165-1190.

LEHRER Ute, KEIL Roger, KIPFER Stephan, 2010, Reurbanisation in Toronto : Condominium boom and social housing revitalization. DisP- The planning Review, 181, p. 81-90.

LUSSAULT Michel, 2007, L’Homme spatial. La construction sociale de l’espace humain, édition du Seuil.

McCORMACK Derek P. and LATHAM Alan, 2009. “Thinking with Images in Non-Representational Cities: Vignettes from Berlin.” Area 41 (3): 252–62. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1475-4762.2008.00868.x.

McNEILL D., 2002, The mayor and the world city skyline: London’s tall buildings debate, International Planning Studies, n°7, p.325-334.

McNEILL D., 2008, The global architect, firms fame, and urban form, London, Routledge, 180p.

MICHON P., 2008, L’opération de régénération des Docklands : entre patrimonialisation et invention d’un nouveau paysage urbain, Revue Géographique de l'Est, vol. 48, n°1-2. URL: https://rge.revues.org/1104.

MOLLÉ G., 2016, Le retour des projets de tours en France s’explique-t-il par une redéfinition des imaginaires verticaux à travers l’innovation immobilière ?, Mémoire de Master 1, Université Lyon 2, 128p. View on Highrise website

MOLLÉ Geoffrey, APPERT Manuel et MATHIAN Hélène, 2019, « Le retour de l’habitat vertical et les politiques TOD (Transit Oriented Development) dans les villes françaises : vers une intensification urbaine socialement sélective ? », Espace populations sociétés [En ligne], n°3, URL: http://journals.openedition.org/eps/9256 ; DOI: https://doi.org/10.4000/eps.9256. View on Highrise website

MONGEARD Laëtitia, BOTEA Bianca et SERRA Lise, 2019, « Connaissances par proximité dans la recherche sur la rénovation urbaine. », EspacesTemps.net [Online], Traverses, URL: https://www.espacestemps.net/articles/connaissances-par-proximite-dans-la-recherche-sur-la-renovation-urbaine/; DOI: 10.26151/espacestemps.net-5ezs-v534.

MONGIN, O., 2005, La condition urbaine ; La ville à l’heure de la mondialisation, Paris : Seuil, 325p.

MONNET J., 2007, La symbolique des lieux : pour une géographie des relations entre espace, pouvoir et identité, Cybergeo: European Journal of Geography, article 56. URL: http://cybergeo.revues.org/index5316.html.

MONTES C., APPERT M., 2015, Skyscrapers and the redrawing of the London skyline: a case of territorialisation through landscape control. Articulo-Journal of Urban Research (Special issue 7). URL: https://articulo.revues.org/2784.

MONTÈS Christian, APPERT Manuel et DROZDZ Martine, 2017, « Enjeux de l'exploration culturelle des hauteurs urbaines », Géographie et cultures [Online], 102, URL: http://journals.openedition.org/gc/5175; DOI: https://doi.org/10.4000/gc.5175.

MOROVICH Barbara, 2014. « Entre stigmates et mémoires : dynamiques paradoxales de la rénovation urbaine », Articulo - Journal of Urban Research [Online], Special issue, n°5. DOI: https://doi.org/10.4000/articulo.2529; URL: https://journals.openedition.org/articulo/2529.

MOROVICH Barbara, 2017, Miroirs anthropologiques et changement urbain, Paris, L’Harmattan, coll. « Anthropologie critique ».

MOUAZIZ-BOUCHENTOUF, N., « Foncier et immobilier a Oran. Législations et stratégies d’acteurs », Université des Sciences et de la Technologie d’Oran - Mohamed Boudiaf, 2014.

MOUAZIZ-BOUCHENTOUF, N., « Les Tours à Oran (Algérie). La Quête de La Hauteur et Ses Conséquences Sur La Ville », Géocarrefour, Vol. 91, n° 2, Gouverner La Ville Verticale : Entre Ville d’exception et Ville Ordinaire, mis en ligne en 2017. URL: https://journals.openedition.org/geocarrefour/10254.

NETHERCOTE Megan and DORIGNON Louise, 2020. “Disorientation in the Unmaking of High-Rise Homes.” Transactions of the Institute of British Geographers n/a (n/a): 1–15. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1111/tran.12427.

NIJHUIS S., VAN DER HOEVEN F., 2012, Developing Rotterdam’s skyline, CTBUH Journal, n°2, p.32-37.

OLIVIER, C., 2017, « Trois tours terribles », Géographie et cultures, vol.102, pp. 121-141.

OVERNEY Laetitia, 2014, « L’épreuve des démolitions à la Duchère : tactiques de résistance d’un collectif d’habitants », in Deboulet, Agnès et Lelévrier, Christine (dir.). Rénovation urbaine en Europe : quelles pratiques ? Quels effets ?, Presses Universitaires de Rennes, collection Villes et Territoires, p. 125-134.

PAQUOT Thierry (ed.), 2007, Habiter, le propre de l’humain. Villes, territoire et philosophie. La Découverte.

PAQUOT Thierry, 2008, La folie des hauteurs, François Bourin, 219 p.

PEREC Georges, 1995, L’infra-ordinaire, Editions du Seuil, Librairie du XXIe siècle, Paris, 121p.

PERRIN Emmanuel, BENTAYOU Gilles, RICHERAL Cyprien, 2015, Contrat d'axe et Transit-Oriented Development : quel renouvellement de l'action publique en matière de mobilité et d'aménagement ? (Point de vue d'acteurs). Flux, 3 (N° 101-102), p. 111-123.

PICON-LEFEBVRE V., CHABARD P., 2013, La Défense, dictionnaire et atlas, 2 volumes, Paris, Parenthèses.

PIERCE Joseph and LAWHON Mary, 2015. “Walking as Method: Toward Methodological Forthrightness and Comparability in Urban Geographical Research.” The Professional Geographer 67 (4): 655–62. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1080/00330124.2015.1059401.

PINNEGAR Simon, RANDOLPH Bill, TROY Laurence, CROMMELIN Laura and EAST-EASTHOPE Hazel, 2020. “Vertical Sprawl in the Australian City: Sydney’s High-Rise Residential Development Boom.” Urban Policy and Research, January, 1–19. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1080/08111146.2019.1709168.

PINSON Gilles, 2010, La gouvernance des villes françaises. P. le Sud, 1 (n° 32), p. 73-92.

POLLARD Julie, 2011, Les groupes d'intérêt vus du local. Real estate developers in the housing sector in France. Revue française de science politique, 4 (Vol. 61), p. 681-705.

POUSIN F., 2007, Du townscape au « paysage urbain », circulation d’un modèle rhétorique mobilisateur, Strates, n°13. URL: http://strates.revues.org/5003

RAULIN Anne, 1997, Manhattan ou la mémoire insulaire, Paris, Institut d'Ethnologie.

RAULIN Anne, 2006, « Manhattan comme une île », Ethnologie française, n°3 Vol. 36, p. 467-474. DOI: 10.3917/ethn.063.0467. URL: https://www.cairn.info/revue-ethnologie-francaise-2006-3-page-467.htm.

RANDOLPH Bill, TROY Laurence, PINNEGAR Simon, CROMMELIN Laura and EAST-EASTHOPE Hazel, 2020. “Vertical Sprawl in the Australian City: Sydney’s High-Rise Residential Development Boom.” Urban Policy and Research, January, 1–19. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1080/08111146.2019.1709168.

RERAT P., 2012, Choix résidentiel et gentrification dans une ville moyenne, Cybergeo, Espace, Société, Territoire, document 579. URL: https://cybergeo.revues.org/24931

RICHERAL Cyprien, BENTAYOU Gilles, PERRIN Emmanuel, 2015, Contrat d'axe et Transit-Oriented Development : quel renouvellement de l'action publique en matière de mobilité et d'aménagement ? (Point de vue d'acteurs). Flux, 3 (N° 101-102), p. 111-123.

ROJON Sarah, 2014, « La rénovation de l’habiter dans le grand ensemble de la Duchère. Pour en finir avec la figure des « nouveaux habitants » », Recherches sociologiques et anthropologiques [Online], 45-1, URL: http://journals.openedition.org/rsa/1132; DOI: https://doi.org/10.4000/rsa.1132.

ROSE Gillian, 2016. Visual Methodologies : An Introduction to Researching with Visual Materials. 4th edition. SAGE Publications Ltd. URL: https://ezp.lib.unimelb.edu.au/login?url=https://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&db=cat00006a&AN=melb.b6202092&site=eds-live&scope=site.

ROSEN G., WALKS A., 2014, Castles in Toronto’s sky: condo-ism as urban transformation, Journal of Urban Affairs, vol. 37, n°3, p.289-310.

ROSSIGNOL C., 2014, Urbanité, mixité et grande hauteur : pour une approche par les dimensions public/privé des tours mixtes et de leur production. Le cas de Paris et l’Ile-de-France, thèse de doctorat sous la direction de Youssef Diab, Leila Kebir et Vincent Becue, EIVP, 382p.

SECOR Anna, 2013, “Urban Geography Plenary Lecture: Topological City”, Urban Geography, 34 (1).

SERRA Lise, BOTEA Bianca et MONGEARD Laëtitia, 2019, « Connaissances par proximité dans la recherche sur la rénovation urbaine. », EspacesTemps.net [En ligne], Traverses, URL : https://www.espacestemps.net/articles/connaissances-par-proximite-dans-la-recherche-sur-la-renovation-urbaine/ ; DOI : 10.26151/espacestemps.net-5ezs-v534

SCOCCIMARRO R., 2017, Naissance d’une skyline: La verticalisation du front de mer de Tokyo et ses implications sociodémographiques, Géoconfluences. URL: http://geoconfluences.ens-lyon.fr/informations-scientifiques/dossiers-regionaux/japon/articles-scientifiques/skyline-verticalisation-tokyo.

SKLAIR Leslie, 2005. “The Transnational Capitalist Class and Contemporary Architecture in Globalizing Cities.” International Journal of Urban and Regional Research 29 (3): 485–500.

SUDJIC D., 2005, The edifice complex: how the rich and powerful shape the world, New York, Penguin and London, Allen Lane.

STAMBOULI, N., 2014, « L’Aéro-habitat, avatar d’un monument classé ? », Livraisons de l’histoire de l’architecture, n° 27, p. 117–127. URL: http://journals.openedition.org/lha/382; DOI: 10.4000/lha.382.

STREBEL Ignaz, CAIRNS Stephen and JACOBS Jane M., 2007. “‘A Tall Storey ... but, a Fact Just the Same’: The Red Road High-Rise as a Black Box.” Urban Studies 44 (3): 609–29. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1080/00420980601131910.

STUART Elden, 2013. “Secure the Volume: Vertical Geopolitics and the Depth of Power.” Political Geography 34: 35–51. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.polgeo.2012.12.009.

TISSOT Sylvie, 2003, “De l'emblème au « problème » : Histoire des grands ensembles dans une ville communiste”, Les Annales de la recherche urbaine, N°93, Les infortunes de l’espace. pp. 122-129.

TROM Danny and BREGVIGLIERI Marc, 2003, « Troubles et tensions en milieu urbain. Les épreuves citadines et habitantes de la ville », in Les sens du public : publics politiques et médiatiques, D. Céfaï et D. Pasquier (dir.), PUF, pp.399-416.

TROY Laurence, RANDOLPH Bill, PINNEGAR Simon, CROMMELIN Laura and EAST-EASTHOPE Hazel, 2020. “Vertical Sprawl in the Australian City: Sydney’s High-Rise Residential Development Boom.” Urban Policy and Research, January, 1–19. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1080/08111146.2019.1709168.

TURKINGTON R., WASSENBERG F. et KEMPEN R. VAN, 2004, High-rise housing in Europe: current trends and future prospects, Delft, DUP Science.

VAN DER HOEVEN F., NIJHUIS S., 2012, Developing Rotterdam’s skyline, CTBUH Journal, n°2, p.32-37.

VESCHAMBRE Vincent, 2011, La rénovation urbaine dans les grands ensembles: de la monumentality to banality? In: Ioana IOSA and Maria GRAVARI-BARBAS, Monumentalité(s) urbaine(s) aux XIXe et XXe siècles. Sens, formes et enjeux urbains, Paris, L'Harmattan, p. 193-206.

VIALA L., 2017, Science-fiction et prospective de l’habiter vertical, Géographie et culture, n°102, p.101-120.

WAIBEL M., 2006, The Production of Urban Space in Vietnam’s Metropolis in the course of Transition: Internationalization, Polarization and Newly Emerging Lifestyles in Vietnamese Society, Trialog, p.43–48.

WALKS A., ROSEN G., 2014, Castles in Toronto’s sky: condo-ism as urban transformation, Journal of Urban Affairs, vol. 37, n°3, p.289-310.

WASSENBERG F., TURKINGTON R. et KEMPEN R. VAN, 2004, High-rise housing in Europe: current trends and future prospects, Delft, DUP Science.

WINNER, 1993 in GRAHAM, S., 2016, Vertical - The City from Satellites to Bunkers. Verso Books, 416p.

ZARECOR K, 2011, Manufacturing a socialist modernity : Housing in Czechoslovakia, 1945-1960, Pittsburgh, The University of Pittsburgh Press, 480p.

ZEMBRI, P., CHAPELON, L., BAVOUX, JJ., BAUCIRE, F., 2005, Géographie des transports, Armand Colin, Paris, 227p.COHEN, J.-L., N. Oulebsir, and Y. Kanoun, Alger : Paysage urbain et architectures, 1800-2000, Editions de l’Imprimeur, Paris, 2003.

ZUKIN Sharon, 1998, Urban Lifestyles : Diversity and Standardisation in Spaces of Consumption, Urban Studies 35 (5-6): 825-839.

Support:

Support: